What is music writing for?

The recent announcement of the (possible) coming demise of Pitchfork, the online music publication, must have seemed like the distant light from a dying star to those of us of a more advanced age.

The recent announcement of the (possible) coming demise of Pitchfork, the online music publication, must have seemed like the distant light from a dying star to those of us of a more advanced age. That was certainly how it seemed to this writer, having first read Pitchfork well over two decades ago as an undergraduate but only rarely in the years since.

The site in that early era was primarily characterized by semi-coherent prose, an interest in introducing readers to records they wouldn’t otherwise know, and gatekeeping snobbery. I don’t really mean the last part as a pejorative, but it’s undeniably true. Keep in mind that in those days they didn’t have much direct access to most of the artists they were covering, even the more obscure ones. Plus, the dissociation from any particular scene cost them the kind of direct pipeline to up-and-comers that local zines once had (despite being originally a Midwestern publication, it was not especially focused on the region, as for example the critics for the Chicago Tribune were).

So while this frequently resulted in egregious snottiness and a general air of juvenilia (which at least some of the writers probably regretted), the upshot is that they could avoid sycophancy and speak directly to potential listeners. In other words, it pretty much lived and died by its reviews, and the site’s real value lay in whether it could introduce you to good music.

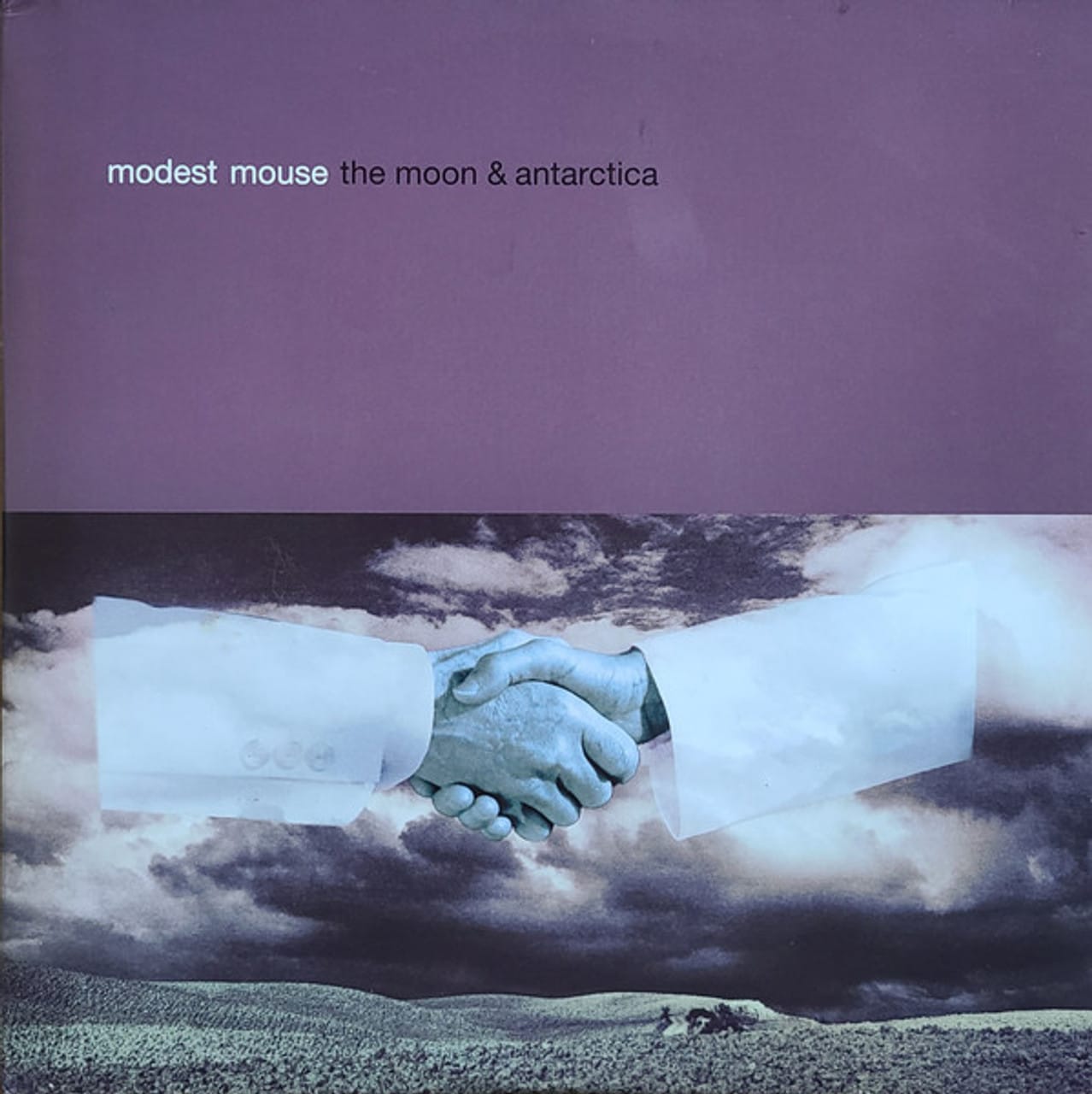

The original review of Modest Mouse’s major-label debut is a fairly telling snapshot of the Pitchfork dynamic. The writing is wildly self-indulgent, the question of selling out is duly raised (a concern that has been effectively dead for at least two decades now), but the album receives a justly superlative rating. And getting that last one right is not nothing. Look, at the end of the day writing about music has its limits (hence the famous analogy to dancing about architecture), but getting you to listen to the right music matters a good deal. Even the best music writing has a way of lapsing into egoism (Lester Bangs), pretentiousness (Greil Marcus), or whatever it is Robert Christgau is doing with those mini-reviews.

Interestingly, reviews of classical music don’t seem to have this problem in the same way, possibly because the dignity and loftiness we ascribe to classical music allows for a commensurate seriousness in discussions without appearing ridiculous. But the reader cannot help but perceive conceptual and tonal gaps when it comes to thousands of words of sincere prose about pop music. Beethoven can have an E.T.A. Hoffmann; the Troggs cannot.

Jazz probably lies somewhere in between, attracting all manner of preciousness but also first-rate writers like Ralph Ellison and Philip Larkin. Of course, even the latter had his prejudices. Having first encountered jazz in its earliest golden days, he remained a partisan of Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet (cf. this wondrous poem), and Bix Beiderbecke, viewing subsequent developments like bebop as signs of decline. Of giants like Miles and Coltrane, he had little good to say. Which in the end is a bit of a problem, because what we want most from music writing is less great writing (though we want that too) but an answer to the eternal question: WHAT SHOULD WE LISTEN TO NEXT? And on this point, quite a few authorities prove unreliable in the end.

Rolling Stone was a particular offender in this regard. In the immortal words of Jason Lee in Almost Famous, it’s the magazine that “trashed ''Layla'', broke up Cream, ripped every album Led Zeppelin ever made…” At the other end of the spectrum, in its senescence, reviewers were known to assign glowing, 5-star reviews to mediocre productions from major artists like Springsteen and U2. And in probably the most notorious instance, founding editor Jann Wenner personally gave one of Mick Jagger’s utterly forgettable solo LPs a perfect rating (namely Goddess in the Doorway, which Jagger’s own bandmate Keith Richards continues to refer to as “Dogshit in the Doorway”). That Wenner had long been obliged to carefully manage his relationship with Jagger owing to the possibly actionable similarities between the name of the former’s periodical and the latter’s band only lends credence to the view that the entire business of reviewing is highly politicized (Joe Hagan's excellent biography of Wenner certainly suggests as much).

The thing is that gatekeeping isn’t really the most important part. But it isn’t negligible either. There’s a great exchange in Tombstone, where Val Kilmer’s Doc Holiday (who is clearly dying of tuberculosis) tells his compatriots that he will stick to the hunt for the outlaws out of friendship to Wyatt Earp. To which one says, “hell, I got lots of friends.” And Holiday simply replies, “I don’t.”

The point is that much like someone who too easily makes friends tends not to be reliable in a pinch, the real trouble with "poptimism" isn’t that it rejects snobbery but that it is hard to trust. It isn’t now so important that Pitchfork (rightly) gave Coldplay’s first record a middling review, but that it was simultaneously able to give distinction to better ones. This to me is the real standard by which I evaluate music writers—allowing for subjectivities in tastes, will I mostly gain from following their advice? Looking back at what I would consider to be some of the very best long players from the last gasp of the album era (which also coincided with Pitchfork’s original rise to prominence), Pitchfork passed this test pretty much with flying colors. Obviously, your mileage may vary, but a non-exhaustive list might include:

Kid A

Yankee Hotel Foxtrot

Emergency and I

The Soft Bulletin

Perfect from Now On

Homogenic

Moon and Antarctica

Is This It

I See a Darkness

Turn On the Bright Lights

I Can Hear the Heart Beating as One

American Water

All of these received at least a 9 out of 10 rating, which is to say they did a pretty good job of identifying future classic (or quasi-classic) albums upon release. (Obviously, there is something silly and arbitrary about this ratings system, but I actually think it's good enough for government.)

Of course, that record has gaps. Comparative blind spots are inevitable. Thus Time (The Revelator) and Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, two of the best American albums released in my lifetime, originally received (respectively) an 8.1 and no review at all that I can see.

Somewhat more notoriously, Pitchfork also basically ignored black music genres for years. I am unable, for example, to find contemporaneous reviews of such personal favorite records as Aquemini, Mama’s Gun, Voodoo, et al.). At some point they did an about-face on this and began providing incredibly obsequious coverage to major stars like Kanye West and Beyoncé, a practice they doubled down on by issuing revised versions of their best-of-the-decade lists for the 80s and 90s, to allow, e.g., Purple Rain to dethrone Daydream Nation. Now, seeing as Prince is hands-down one of my favorite-ever artists, I have no personal problem with this, but one can’t help but find the whole business a bit suspect.

Worse still is the rather Soviet practice of allowing most of their original 90s reviews to be wiped altogether and frequently replaced by updated versions that incorporate hindsight (or sensitivities) previously unavailable. I was in fact unable to link reviews for several albums on the above list, because the original reviews have since vanished, and my appetite for trawling through the Wayback Machine is limited (Reddit at least confirms their prior existence, so I am reasonably certain I didn't hallucinate them).

Some of this was likely a craven response to larger cultural shifts that started to take place around 2013 or so, in which insufficient representation of certain racial and sexual minorities came to be perceived as evidence of prejudice. But I suspect some of it was just the impulse to be all things to all people. Pitchfork originated as a defiantly indie-centric publication, likely benefiting from the post-grunge efflorescence of American rock—above all the fin de siècle New York scene chronicled so entertainingly in Meet Me in the Bathroom.

That era was perhaps the last time we saw robust local or regional music scenes that could emerge organically while still flying somewhat under the larger cultural radar. To give a sense of context here, The Strokes--unquestionably the breakout act of the early-oughts New York indie scene--ultimately sold about 2 million copies of their now-classic debut album. A perfectly respectable number representing approximately half of the sales of Matchbox 20's second album, released around the same time. And just to be clear, that was the Matchbox 20 album that wasn't considered a hit.

This situation gave left-field music criticism a certain raison d'être, which eroded with the decline of the album-as-art-form and the blurring of genre and popular/indie divides. Somewhat ironically, both trends were very much products of the same internet-based model which allowed Pitchfork to achieve prominence in the first place. Perhaps as a result, while the writing itself really did improve a great deal, it increasingly seemed to ratify an existing consensus about popular music instead of inculcating new tastes in their readership.

Nonetheless, I think its motto, “the most trusted voice in music,” while obviously an exercise in self-promotion, had the right idea in theory. The writer/reviewer wants above all to be trusted, and the reader wants to be able to trust. It is no surprise then that we now routinely hear the exhortation “trust the algorithm” at a time when music—and for that matter all consumer—recommendations are primarily offered algorithmically through one’s preferred streaming service. But trust, going back to its etymological root, is a kind of faith. Our faith in people derives from the observation of their judgment and virtue. And part of the magic of a great recommendation is that it gives you something you didn’t know you wanted—it is the product of an independent mind rather than a pale reflection of our own as inferred from our past choices by ever-watchful machines. We learn over time to trust such independent minds (and ears), as they expand our sense of auditory pleasure.

Knowledgeable friends, older brothers, cool uncles, and others are all standard resources, but this represents a limited network, not to say one that not everyone enjoys to begin with. In any case, even in a world of Taylor Swiftian hegemony and self-cannibalizing streaming services, there’s still good music to be heard and connoisseurs to direct us to it.

Might I recommend Aquarium Drunkard?