Mapping the Global South

These days a similar condescension is more likely to be applied to a different end of a compass point. I am referring, of course, to the so-called “Global South”—a loose, collective term for the world’s have-nots that has recently regained currency.

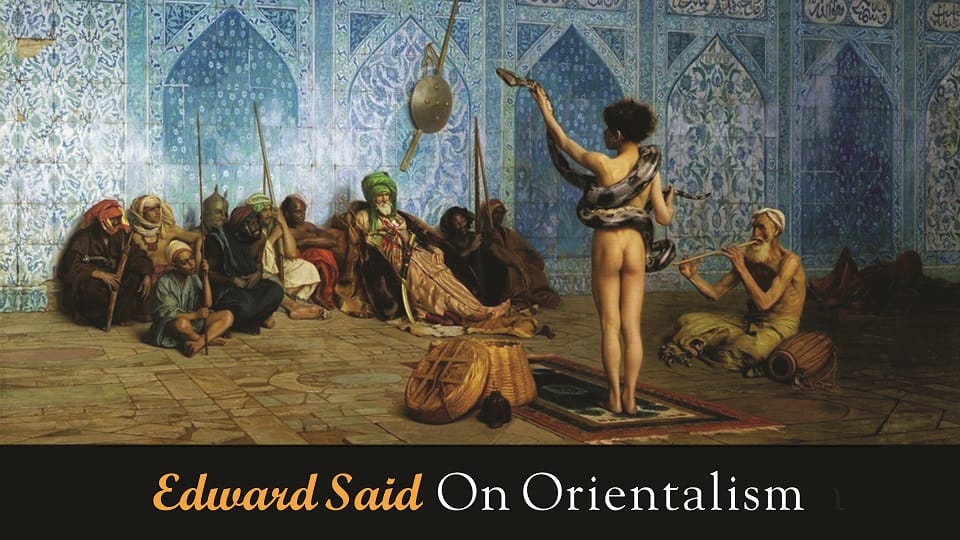

Nearly half a century ago, in what remains one of the most influential works of critical theory, Edward Said coined the term “Orientalism” in his book of the same name. Said understood this to mean something like a patronizing (and often romanticized) mental picture that Europeans superimposed upon the real societies of the Middle East and Asia. It was not incidental to Said that this mode of thinking existed in support of colonial institutions, but one has the sense that its inherent condescension was going to be a problem either way (this is not the place to get into the many challenges to his thesis, but see here and here).

These days a similar condescension is more likely to be applied to a different end of a compass point. I am referring, of course, to the so-called “Global South”—a loose, collective term for the world’s have-nots that has recently regained currency. As this useful summary (which also takes issue with the term) points out, unlike many buzzwords, usage of Global South has ascended from academia up the bureaucratic ranks to the point that the U.N. Secretary-General, President of the World Bank and President Biden, among other world leaders, have all employed it. This is hardly an indication of seriousness, but it does suggest a certain staying power.

At any rate, the "Global South" is now routinely invoked by commentators both as a meaningful agent of geopolitical action and as an audience (and jury) for the actions of the Anglo and European powers, and whose collective views the latter are now obliged to take into account. Indeed it appears to have been become ubiquitous enough to provoke a mild backlash among centrist types:

Is "the Global South" a term that's used by any remotely normal people anywhere in the world, or is this like strictly grad school lingo?

— Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) March 4, 2024

The term has in fact hung around for decades, having originated during the Cold War, though at the time the now-disfavored “Third World” was more commonly used to refer to the developing nations that were not formally allied to one of the two great power blocs of the time—and were in fact frequently arenas of geopolitical competition. That term has since declined: partly due to being vaguely politically incorrect, and partly due to the disappearance of the Cold War context that once made it comprehensible. But does Global South represent any kind of improvement?

To begin with, it has to be noted that aside from being vague and impossibly general, it’s technically not even accurate. Applying to such countries as Yemen (15.5527° N, 48.5164° E), Malaysia (4.2105° N, 101.9758° E), Argentina (38.4161° S, 63.6167° W), etc. but not, however, Australia—a country so obviously southern that its name literally means “southern land.” (For that matter, Antarctica, which straddles the South Pole itself, seems to be neither here nor there.)

At the same time, the Global South manages to encompass countries as varied as Burundi (Surface area: 27,834 km²; Population: 12.89 million; GDP: 3.33 billion USD; Nuclear stockpile: 0) and India (Surface area: 3.287 million km²; Population: 1.417 billion; GDP: 3.417 trillion USD; Nuclear stockpile: 160 warheads). It is difficult in sum to discern precisely what characterizes this menagerie of jurisdictions. To put it a bit ungenerously, one begins to suspect that this is something like the geopolitical counterpart to “POCs”—another loose aggregate primarily defined by what it is not. Moreover, much like that term, it has gained currency among a certain commentariat class, whose attraction to trendy concepts exceeds their critical thinking skills. (There is also an unavoidable element of condescension in all this, which is not necessarily a bad thing when combined with some sense of noblesse oblige. But here, alas, little responsibility is assumed by the speaker whose role is to somehow interpret the preferences of roughly half the planet to well-heeled audience, while enjoying the commission of professional advancement in the exchange.)

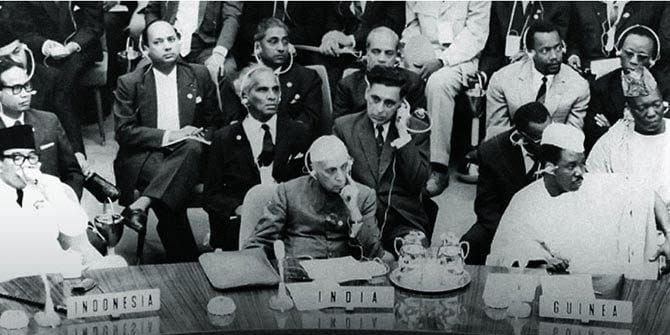

The larger question thus remains: can the Global South really "act" in a manner that has real geopolitical impact? As it happens, it (or some version of it) has sought to do so before, when a coterie of representatives of formerly colonized powers sought to become players on the stage of the Cold War. Paul Johnson termed this group the “Bandung Generation,” named after the titular Afro-Asian Conference held in April 1955 in Indonesia, which hosted luminaries from across the developing world, including Indonesia’s own President Sukarno, India’s Jawaharlal Nehru, China’s Zhou En-Lai, Egypt’s Gamal Abdul Nasser, and Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, among others. The purpose of the conference was notionally to pursue actual goals of economic development and decolonization but perhaps tacitly to project widely the flattering collective image key leaders had devised for their states.

As Johnson put it:

There was the first world of the West, with its rapacious capitalism; the second world of totalitarian socialism, with its slave-camps; both with their hideous arsenals of mass-destruction. Why should there not come into existence a third world, arising like a phoenix from the ashes of empire, free, pacific, non-aligned, industrious, purged of capitalist and Stalinist vice, radiant with public virtue, today saving itself by its exertions, tomorrow the world by its example? Just as, in the nineteenth century, idealists had seen the oppressed proletariat as the repository of moral excellence - and a prospective proletarian state as Utopia - so now the very fact of a colonial past, and a non-white skin, were seen as title-deeds to international esteem. An ex-colonial state was righteous by definition. A gathering of such states would be a senate of wisdom.

More succinctly, Sukarno as host stated in his opening address: “We, the peoples of Asia and Africa, 1,400,000,000 strong, far more than half the human population of the world, we can mobilise what I have called the Moral Violence of Nations in favour of peace.”

It's still difficult to say exactly what he meant there, but the Bandung Generation's ambitions had less to do with flowery rhetoric than with two broader inter-linked global dynamics: the retreat of the colonial empires and the geopolitical competition between the Western and Soviet alliances.

For the real payoff there was not solidarity but “non-alignment”—i.e., positioning themselves to deal with the two superpowers from an advantageous standpoint. A nominal position of neutrality generally offered greater leverage in such dealings than alliance, which often resulted in being taken for granted—hence the remark attributed to Henry Kissinger that "it may be dangerous to be America's enemy, but to be America's friend is fatal." Further, non-alignment would notionally allow the states that adopted it to play the greater powers off against one another, bidding up the value of aid and trade relationships while bidding down their own obligations. In the end, the reality was that their collective interests were vague and amorphous, and their several interests led them either into conflict with one another and/or to tacitly align themselves with one or the other of the world’s great powers as conditions dictated.

Now, the countries of the Global South are presently more fortunate than they formerly were under whatever name. First, the end of the Cold War eliminated many (though certainly not all) of the incentives for foreign meddling by diplomatic or military means. It also reduced both the appeal and material support for the pathological ideologies that flourished during the previous era, primarily on the left. Second, those same countries are far less likely these days to feature charismatic leaders wielding their personal influence for highly destructive outcomes. Some of this is linked to the same dynamic as above, in that much of the charisma of the major 20th-century political figures of the developing world was bound up with their espousal of revolutionary ideologies. But whatever the cause, the replacement of charismatic firebrands with Western-educated technocrats has generally been a positive development, even when the latter have proven largely ineffectual or even corrupt, as neither have done as much damage as the schemes of a Nasser or a Nyerere.

If there is continuity between the two eras, it will have to do with the fact that during the Cold War the marginal countries' choices were determined by national interests as they understood them, not by some collective good, and there’s little reason to expect that the nations comprising the Global South today will operate differently. And insofar as they invoke that concept it will be for largely instrumental purposes. As Otto von Bismarck said, “I have always found the word Europe on the lips of those politicians who wanted something from other Powers which they dared not demand in their own names.”

The problem remains, however, that this way of speaking betrays a belief in eternal categories of victim and victimizer such that the experience of European colonialism takes primacy over other political events before or since. For as Machiavelli reminds us, when it comes to politics, all things are in motion. Leaving aside the question of whether the People's Republic of China enjoys real historical continuity with imperial China, is China more victimized or victimizer over the course of the past half millennium?

The history of world politics is replete with servants who became masters going back to the Persians under Cyrus. If certain states acquire great power status, then that status will simply be more salient than any prior situation of subjugation (obviously a collective memory of past subjugation can remain a source of national identity, but this is not objectively more consequential than a nation's present material capabilities).

It is frankly difficult to disentangle these considerations from the discourse of decolonization which pervades academia and has come to inform the default understanding of journalists, government bureaucrats, and staffers of both NGOS and IGOs (a frequently interchangeable bunch). And it is due to the prevalence of this understanding that the colonial experience is still assigned such importance when it comes to understanding our world today. This is not to say it merits no consideration, but it is rather begging the question to grant the legacy of colonialism priority over, e.g. the prior history of Chinese and Indian civilizations or the demographic future of sub-Saharan Africa when it comes to thinking about 21st century geopolitics.

Now it must be said that when it comes to geopolitics, which necessarily involve vast and often disparate phenomena, a certain imprecision is inevitable, and in this respect the bagginess of the Global South concept only follows in the legacy of a tradition that has already given us Clashes of Civilizations, Heartlands and Rimlands, Soft Power, Thucydides Traps, Polycrises, and more. And while these are all easy to mock, even such essential concepts like “state system” cannot help but abstract from concrete realities to a certain degree.

And this is perhaps the real trouble with the phrase: that it is yet more evidence of how our elites remain beholden to gaseous imprecise thought and speech. But wait, you say. Are these terms not by now global in their usage? And more broadly has the cast of mind that could produce and repeat such terms not become more or less globalized? After all, you can land your plane Thomas Friedman-style in New Delhi, Berlin, Washington or Canberra and you’ll hear much the same species of patter.

Perhaps this is the real irony of the proliferation of a term like “Global South”: that it represents not so much a display of newfound authority by former subalterns, but rather further proof of American hegemony even as its relative material power may be in decline. It’s not that other nations may not be prone to their own species of bullshit (the French have been known to produce it in great volumes), but it is telling how much they have come to parrot that particularly American version of empty consultant-speak with concepts that sound like branding statements on LinkedIn. Such terms practically come with their own PowerPoint slides.

Meanwhile, trendy slogans aside, we continue to live in a world defined by nation-states rather than cardinal directions. It’s not that a state (or states) that lie between the temperate zones can’t make its interests felt on the international scene, but in the end, it will be a reflection of that state’s interests, not of some broader moral or geopolitical outlook conditioned by one’s relation to the angles of the Sun’s rays.